Why We Need to Generate Lots of Ideas

Gray Somerville

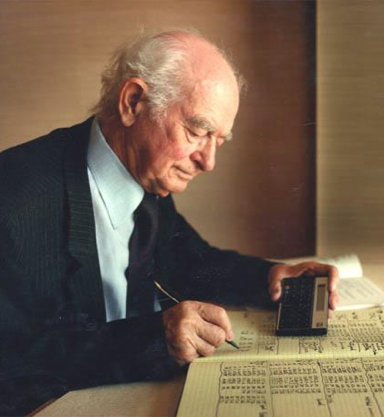

Linus Pauling, a famous American scientist and two-time winner of the Nobel prize, once commented that, “the best way to get a good idea is to get a lot of ideas and throw the bad ones away.”

That said, research indicates that most of us fail to follow Pauling’s advice. Rather than generating lots of ideas, we tend to content ourselves with the first few thoughts that come to mind, possibly because we just don’t see the point of continuing to think about an issue once a reasonably good idea is on the table. If you or your team have been guilty of ideation under-achievement, here are three good reasons to raise your ambitions:

- Our first ideas are typically just memories of old ideas,

- It’s only after wringing out the old ideas that new ideas can flow in, and

- We get a huge return on the time and effort we invest in ideation.

Let’s examine each of these points in a little more detail, starting with the claim that first ideas are just memories of old ideas.

#1 First Ideas Are Just Memories of Old Ideas

Where do ideas come from? For example, if presented with an incomplete word like “n-__-r-s-e,” how does our mind fill in the blank?

The short answer is pattern matching. At some point in our life we saw this pattern of letters for the very first time and had to struggle to make sense of it as our brain wired together a whole new configuration of neurological activity. But the next time we saw it, the answer came a little faster, and then a little faster, and then a little faster still until a memory was formed – an automatic firing of a particular set of brain cells that instantly and effortlessly made sense of this pattern.

So, what in fact is the missing letter? There’s a surprisingly long list of correct answers including:

- “A” as in “narse,” which is both an acronym for the National Association of Retired Sears Employees and also a British slang term for “nasty.”

- “E” as in “Nerse,” a village in India.

- And of course, “o” as in “norse,” the Norwegian people and tongue.

But the first idea that came to mind was probably “u” as in nurse because that, by far, is the most common of these four words. In fact, when I do a Google search on these terms, here are the number of web pages that are returned for each:

- 700 million web pages have the word “n-u-r-s-e,”

- 63 million include “n-o-r-s-e,”

- Two million contain “n-a-r-s-e,” and

- Only one million have the word “n-e-r-s-e.”

Since the word “n-u-r-s-e” occurs roughly ten times more often than the word “n-o-r-s-e,” you are about ten times more likely to fill in the blank with a “u” than an “o.” Now consider your profession. You have spent years and perhaps even decades developing and reinforcing particular patterns of thought. You’ve developed an entire vocabulary that is unique to your industry. Concepts that once felt impossible to understand now seem perfectly obvious. And so, if you’re a hotel operator and are asked, “How might we accommodate a surge in tourism?” your mind immediately delivers the answer, “More hotels!” not “AirBnB.” If you’re a taxi operator and are asked, “How might we improve transportation services, your first thought is, “More taxis!” not “Uber. Thoughts become patterns of thought, a well-worn path through the circuitry of our brains.

And after years of working within a given profession, company, or industry, those well-worn paths may even become ruts within which our minds are stuck.

#2 Wring Out the Old Ideas to Let New Ideas Flow In

So, how do we break out of these ruts? We can’t prevent our minds from presenting familiar ideas – the process is automatic. What can we do?

One practical solution is to challenge ourselves to produce more ideas than seems possible. This exercise effectively wrings out the old ideas and allows new insights to flow in. For example, imagine that rather than asking you to fill in the missing letter of the word “n-_-r-s-e,” I had challenged you to come up with at least ten acceptable options for filling in the blank? Immediately you would have seen the letter “u,” and seconds after that you would have identified the letter “o.” But then, you would have had to get creative. Perhaps you would have done a Google search, as I did, or started to re-imagine the string of letters as something other than a word – for example an acronym, a password, or perhaps even as some abstract artistic expression. By challenging your mind to go beyond the boundaries of what seems possible, you force yourself to make new connections, to see things you hadn’t seen before, to have new ideas.

#3 Generating Ideas is One of Our Best Investments

Our third and final reason for generating more ideas is the simple fact that ideation produces a huge return on investment. Generating an idea takes minutes; executing an idea can take years. Before committing ourselves to the long, hard work of testing, refining, and scaling a new concept, we need to make sure we’ve gotten our best insights onto the table. With just a little more effort, we can often find a better idea – an idea that dramatically speeds the pace, reduces the cost, and amplifies the impact of our innovation projects.

Takeaways

So, here are the takeaways:

- Our first ideas are just memories of old ideas

- By generating more ideas than we think possible, we wring out the old ideas and let new insight flow in, and

- The cost of generating more and better ideas is tiny compared to the benefits of a good idea.